fertilizer

hobbitmom

17 years ago

Related Stories

GARDENING GUIDESGet on a Composting Kick (Hello, Free Fertilizer!)

Quit shelling out for pricey substitutes that aren’t even as good. Here’s how to give your soil the best while lightening your trash load

Full Story

GARDENING GUIDESHow to Keep Your Citrus Trees Well Fed and Healthy

Ripe for some citrus fertilizer know-how? This mini guide will help your lemon, orange and grapefruit trees flourish

Full Story

GARDENING GUIDESCommon Myths That May Be Hurting Your Garden

Discover the truth about fertilizer, soil, staking and more to keep your plants healthy and happy

Full Story

GARDENING GUIDESHow to Switch to an Organic Landscape Plan

Ditch the chemicals for a naturally beautiful lawn and garden, using living fertilizers and other nontoxic treatments

Full Story

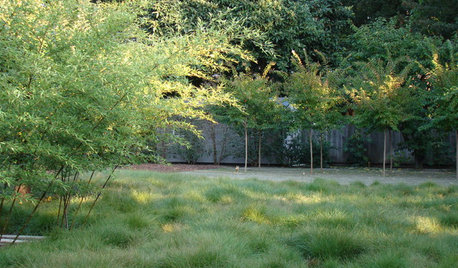

LANDSCAPE DESIGNA Guide to the Grasses Available for Nontraditional Lawns

New grass mixes are formulated to require less water and less fertilizer

Full Story

GARDENING GUIDES5 Prairie Wildflowers That Can Heal Your Soil

Get free, organic soil fertilizer with nitrogen-pumping plants that draw pollinators too

Full Story

REGIONAL GARDEN GUIDESSoutheast Gardener's September Checklist

Fertilize strawberries, plant a tree or two and beckon hummingbirds to your Southern garden this month

Full Story

GARDENING GUIDESSouthwest Gardener's February Checklist

Orange you glad for a citrus-fertilizing reminder? And don't forget the recommended doses of vegetable seeds and cold-hardy flowers

Full Story

GARDENING GUIDESSouthwest Gardener's August Checklist

Manage monsoon effects, remember to fertilize and don't let the heat deter you from planting for fall

Full Story

GARDENING GUIDESPacific Northwest Gardener: What to Do in September

Put in cool-weather veggies, fertilize your lawn and tidy the garden this month before chilly weather arrives

Full Story

morz8 - Washington Coast

rhodyman

Related Professionals

Middle Island Landscape Architects & Landscape Designers · Mitchellville Landscape Architects & Landscape Designers · Roxbury Crossing Landscape Architects & Landscape Designers · Harvey Landscape Architects & Landscape Designers · Middletown Landscape Contractors · Clearlake Landscape Contractors · El Sobrante Landscape Contractors · Essex Landscape Contractors · Middletown Landscape Contractors · Monterey Landscape Contractors · Palos Verdes Estates Landscape Contractors · Rockland Landscape Contractors · Shoreview Landscape Contractors · West Chester Landscape Contractors · Yukon Landscape ContractorsEmbothrium

rhodyman

Embothrium

gardengal48 (PNW Z8/9)

rhodyman

Embothrium

gardengal48 (PNW Z8/9)

rhodyman

rhodyman

gardengal48 (PNW Z8/9)

rhodyman

Embothrium

rhodyman

gardengal48 (PNW Z8/9)

Embothrium

rhodyman

railroadrabbit

rhodyman