help diagnosing problem with my rhodie

applekin

17 years ago

Related Stories

MOST POPULAR7 Ways to Design Your Kitchen to Help You Lose Weight

In his new book, Slim by Design, eating-behavior expert Brian Wansink shows us how to get our kitchens working better

Full Story

LIFE12 Effective Strategies to Help You Sleep

End the nightmare of tossing and turning at bedtime with these tips for letting go and drifting off

Full Story

HOUSEKEEPINGWhat's That Smell? What to Do About Stinky Furniture

Learn how to diagnose and treat pet and other furniture odors — and when to call in a pro

Full Story

DECORATING GUIDESFrom Queasy Colors to Killer Tables: Your Worst Decorating Mistakes

Houzzers spill the beans about buying blunders, painting problems and DIY disasters

Full Story

HOUSEKEEPINGWhat's That Sound? 9 Home Noises and How to Fix Them

Bumps and thumps might be driving you crazy, but they also might mean big trouble. We give you the lowdown and which pro to call for help

Full Story

DECORATING GUIDESHow to Work With a Professional Organizer

An organizing pro can help you get your house together. Here's how to choose the right one and gain your own clutter-clearing skills

Full Story

LIVING ROOMS8 Reasons to Nix Your Fireplace (Yes, for Real)

Dare you consider trading that 'coveted' design feature for something you'll actually use? This logic can help

Full Story

LIFE8 Ways to Make an Extra-Full Nest Work Happily

If multiple generations or extended family shares your home, these strategies can help you keep the peace

Full Story

GARDENING GUIDESHow to Keep Your Citrus Trees Well Fed and Healthy

Ripe for some citrus fertilizer know-how? This mini guide will help your lemon, orange and grapefruit trees flourish

Full Story

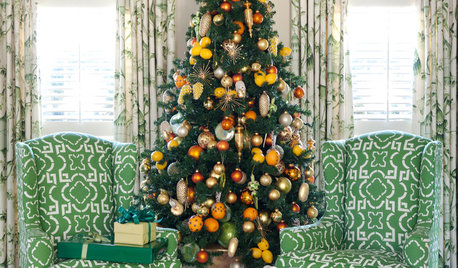

CHRISTMASReal vs. Fake: How to Choose the Right Christmas Tree

Pitting flexibility and ease against cost and the environment can leave anyone flummoxed. This Christmas tree breakdown can help

Full StorySponsored

jean001

Embothrium

Related Professionals

Lake Oswego Landscape Architects & Landscape Designers · Oatfield Landscape Architects & Landscape Designers · Bedford Heights Landscape Contractors · Brookline Landscape Contractors · Cordele Landscape Contractors · East Patchogue Landscape Contractors · Glendale Heights Landscape Contractors · Hawthorne Landscape Contractors · Lake Worth Landscape Contractors · Longview Landscape Contractors · Mastic Beach Landscape Contractors · Mendota Heights Landscape Contractors · Ridgewood Landscape Contractors · Seminole Landscape Contractors · Weslaco Landscape Contractorsgardengal48 (PNW Z8/9)

rhodyman

Embothrium

rhodyman

morz8 - Washington Coast

jean001

applekinOriginal Author

jean001

rhodyman

echalmers

rhodyman