Tap roots

cath41

14 years ago

Related Stories

GARDENING AND LANDSCAPINGGardens Tap Into Rill Water Features

Rooted in ancient design, this water feature is popular again as a way to help contemporary landscapes flow

Full Story

LIFETracing the Deep Roots of Design

Are our design choices hardwired? Consider the lasting appeal of forms from the hunter-gatherer life

Full Story

STORAGETap Into Stud Space for More Wall Storage

It’s recess time. Look to hidden wall space to build a nook that’s both practical and appealing to the eye

Full Story

KITCHEN DESIGNTap Into 8 Easy Kitchen Sink Updates

Send dishwashing drudgery down the drain with these ideas for revitalizing the area around your kitchen sink

Full Story

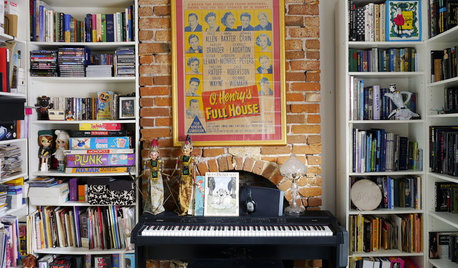

ECLECTIC HOMESMy Houzz: A Cottage With Cozy Charm and Show Biz Treasures

A Melbourne, Australia, home displays its owner’s theatrical roots and eclectic style

Full Story

EVENTSIn Connecticut, a Midcentury Legacy Evolves for Modern Times

A May house tour taps into New Canaan’s rich repository of modernist homes and contemporary designs

Full Story

LANDSCAPE DESIGN8 Modern-Day Moats That Float Our Boats

See how a simple water barrier with ancient roots can make for an eye-catching contemporary garden feature

Full Story

GARDENING GUIDESWhen and How to Plant a Tree, and Why You Should

Trees add beauty while benefiting the environment. Learn the right way to plant one

Full Story

GARDENING GUIDESThe Art of Green Mulch

You can design a natural garden that doesn’t rely on covering your soil with wood and bark mulch

Full Story

EDIBLE GARDENSNatural Ways to Get Rid of Weeds in Your Garden

Use these techniques to help prevent the spread of weeds and to learn about your soil

Full StorySponsored

Your Custom Bath Designers & Remodelers in Columbus I 10X Best Houzz

More Discussions

tapla (mid-Michigan, USDA z5b-6a)

cath41Original Author

Related Professionals

Maple Heights Landscape Architects & Landscape Designers · Jackson Landscape Contractors · Avocado Heights Landscape Contractors · Arden-Arcade Landscape Contractors · Paso Robles Landscape Contractors · West Orange Landscape Contractors · Crowley Landscape Contractors · Solana Beach Decks, Patios & Outdoor Enclosures · Vandalia Decks, Patios & Outdoor Enclosures · Phoenix Fence Contractors · Hayward Fence Contractors · Palo Alto Fence Contractors · Paramount Fence Contractors · Pennsauken Fence Contractors · Prior Lake Fence Contractorstapla (mid-Michigan, USDA z5b-6a)

cath41Original Author

botanicalbill

tapla (mid-Michigan, USDA z5b-6a)

cath41Original Author