carnations

bears48

17 years ago

Related Stories

DECORATING GUIDESTop 10 Interior Stylist Secrets Revealed

Give your home's interiors magazine-ready polish with these tips to finesse the finishing design touches

Full Story

FEEL-GOOD HOME9 Smells You Actually Want in Your Home

Boost memory, enhance sleep, lower anxiety ... these scents do way more than just smell good

Full Story

SPRING GARDENINGTop 10 Scented Plants for Your Garden

A palette of perfumed plants can transform even the smallest of gardens into a sensory delight

Full Story

PINKThe Pink Link — Learn the Secrets of a Decorating Darling

Is it the kiss of death for masculine rooms? Can it soothe a psyche? Discover the history and theories behind this delightful color

Full Story

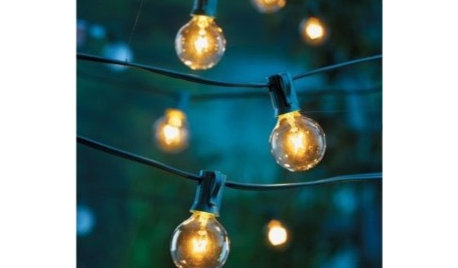

PRODUCT PICKSGuest Picks: Stretch Out Summer With Outdoor Lights

Don't let shorter days spoil the party. String lights, flameless candles and lanterns can brighten patios beyond summer

Full Story

DECORATING GUIDESHandmade Home: The Paper Pompom

Put your own spin on these fluffy, pretty paper poufs for parties, dinners or year-round décor

Full Story

SHOP HOUZZShop Houzz: Style Flowers Like a Pro

The right tools, creative vessels and tips make arranging flowers easy

Full Story

DECORATING GUIDESDecorating Advice to Steal From Your Suit

Create a look of confidence that’s tailor made to fit your style by following these 7 key tips

Full Story

COLORBathed in Color: When to Use Pink in the Bath

Even a sophisticated master bath deserves a rosy outlook. Here's how to do pink with a grown-up edge

Full Story

DECORATING GUIDESHouzz Call: Show Us Your Christmas Tablescape

Do you bring out the good silver, candles, berries and greens for your holiday table? If so, we'd like to see it

Full StorySponsored

Franklin County's Custom Kitchen & Bath Designs for Everyday Living

More Discussions

dogdaze3001

shadowflower13

Related Professionals

Camas Landscape Architects & Landscape Designers · Eden Prairie Landscape Architects & Landscape Designers · Kenmore Landscape Architects & Landscape Designers · Wilmington Landscape Contractors · El Reno Landscape Contractors · Lorain Landscape Contractors · Ringwood Landscape Contractors · San Carlos Park Landscape Contractors · Shoreview Landscape Contractors · Uxbridge Landscape Contractors · Hayward Carpenters · Livingston Carpenters · Clermont Fence Contractors · East Haven Fence Contractors · Salt Lake City Fence ContractorsFrozeBudd_z3/4