pics of tomatoes from Amish Paste x Roman Candle graft

touchstone_the_clown

18 years ago

Related Stories

EDIBLE GARDENSSummer Crops: How to Grow Tomatoes

Plant tomato seedlings in spring for one of the best tastes of summer, fresh from your backyard

Full Story

MOST POPULAR11 Nominees for the ‘She Shed’ Hall of Fame

These special sanctuaries let busy women get away from it all without leaving the backyard

Full Story

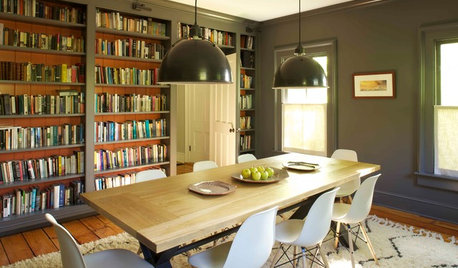

DECORATING GUIDES12 Deadly Decorating Sins

Are your room designs suffering from a few old habits? It may be time to change your ways

Full Story

LANDSCAPE DESIGNWhat Kind of Gardener Are You? Find Your Archetype

Pick from our descriptions to create a garden that matches your personality and tells your story

Full Story

HOUZZ CALLShow Us the Best Kitchen in the Land

The Hardworking Home: We want to see why the kitchen is the heart of the home

Full Story

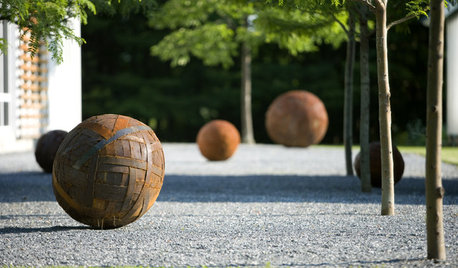

LANDSCAPE DESIGNHow to Create an Unforgettable Garden

Make an impression that will linger long after visitors have left by looking for the possibilities and meaning in your landscape

Full Story

STUDIOS AND WORKSHOPSCreative Houzz Users Share Their ‘She Sheds’

Much thought, creativity and love goes into creating small places of your own

Full Story

GARDENING AND LANDSCAPINGBid Bad Garden Bugs Goodbye and Usher In the Good

Give ants their marching orders and send mosquitoes moseying, while creating a garden that draws pollinators and helpful eaters

Full Story

DECORATING GUIDESA Glimmer of Gold Leaf Will Make Your Room Shine

Make a unique, unexpected statement in any space with this precious metallic finish

Full Story

FEEL-GOOD HOME21 Ways to Waste Less at Home

Whether it's herbs rotting in the fridge or clothes that never get worn, most of us waste too much. Here are ways to make a change

Full StoryMore Discussions

geoforce

admmad

Related Professionals

Mountain Brook Landscape Architects & Landscape Designers · Canby Landscape Contractors · Cockeysville Landscape Contractors · Lakewood Landscape Contractors · New Braunfels Landscape Contractors · Hueytown Landscape Contractors · Carlsbad Carpenters · Maplewood Carpenters · Oak Grove Carpenters · San Marcos Carpenters · Arcadia Fence Contractors · Holbrook Fence Contractors · Kansas City Fence Contractors · Palm Harbor Fence Contractors · Woodland Fence Contractorsadmmad

touchstone_the_clownOriginal Author

touchstone_the_clownOriginal Author

admmad

touchstone_the_clownOriginal Author

admmad

touchstone_the_clownOriginal Author

admmad

touchstone_the_clownOriginal Author

keking

admmad

keking

Elakazal

admmad

keking

admmad

keking

admmad

admmad

keking

admmad

keking

admmad

keking

admmad

touchstone_the_clownOriginal Author

vodreaux